Arqueologia, Historia Antigua y Medieval - Terrae Antiqvae

Red social de Arqueologos e Historiadores

Una nueva herramienta arqueométrica: La datación por rehidroxilación

FIRE AND WATER REVEAL NEW ARCHAEOLOGICAL DATING METHOD

20 May 2009

Scientists at The University of Manchester have developed a new way of dating archaeological objects –using fire and water to unlock their ‘internal clocks’. The simple method promises to be as significant a technique for dating ceramic materials as radiocarbon dating has become for organic materials such as bone or wood.

A team from The University of Manchester and The University of Edinburgh has discovered a new technique which they call ‘rehydroxylation dating’ that can be used on fired clay ceramics like bricks, tile and pottery.

Working with The Museum of London, the team has been able to date brick samples from Roman, medieval and modern periods with remarkable accuracy.

They have established that their technique can be used to determine the age of objects up to 2,000 years old – but believe it has the potential to be used to date objects around 10,000 years old.

The method relies on the fact that fired clay ceramic material will start to chemically react with atmospheric moisture as soon as it is removed from the kiln after firing. This continues over its lifetime causing it to increase in weight – the older the material, the greater the weight gain.

In 2003 the Manchester and Edinburgh team discovered a new law that precisely defines how the rate of reaction between ceramic and water varies over time.

The application of this law underpins the new dating method because the amount of water that is chemically combined with a ceramic provides an ‘internal clock’ that can be accessed to determine its age.

The technique involves measuring the mass of a sample of ceramic and then heating it to around 500 degrees Celsius in a furnace, which removes the water.

The sample is then monitored in a super-accurate measuring device known as a microbalance, to determine the precise rate at which the ceramic will combine with water over time.

Using the time law, it is possible to extrapolate the information collected to calculate the time it will take to regain the mass lost on heating – revealing the sample’s age.

They have calculated that a Roman brick sample with a known age of around 2,000 years was 2,001 years old. A further sample with a known age of between 708 and 758 years was calculated to have an age of 748 years.

The researchers also tested a ‘mystery brick’, with the real age only revealed to them once they had completed their process. This known age was between 339 and 344 years – and the new technique suggested the brick was 340 years old.

During the course of their research, the team also found that ceramic objects have their internal date clocks reset if they are exposed to temperatures of 500 degrees Celsius. Used on medieval brick from Canterbury, the technique repeatedly dated a sample as being 66 years old. Further investigation revealed that Canterbury was devastated by incendiary bombs and fires during a Second World War blitz in 1942. The intense heat generated by the bombing had reset the dating clock by effectively re-firing the bricks. The results also proved accurate enough to show that a brick sample from the King Charles building in Greenwich came from reconstruction carried out in the 1690s and not from the original building which was constructed between 1664 and 1669.

Lead author Dr Moira Wilson, Senior Lecturer in the School of Mechanical, Aerospace and Civil Engineering (MACE), said: “These findings come after many years of hard work. We are extremely excited by the potential of this new technique, which could become an established way of determining the age of ceramic artefacts of archaeological interest.

The method could also be turned on its head and used to establish the mean temperature of a material over its lifetime, if a precise date of firing were known". This could potentially be useful in climate change studies.

“As well as the new dating method, there are also more wide-ranging applications of the work, such as the detection of forged ceramic.”

The three-year £100,000 project was funded by the Leverhulme Trust, with the microbalance - which measures mass to 1/10th of a millionth of a gram – funded by a £66,000 grant from the Engineering and Physical Science Research Council (EPSRC).

Researchers are now planning to look at whether the new dating technique can be applied to earthenware, bone china and porcelain.

Notes for editors

For more information please contact Alex Waddington, Media Relations Officer, the University of Manchester, 0161 275 8387 / 07717 881569. Dr Wilson is available for comment by arrangement.

The paper, entitled ‘Dating fired-clay ceramics using long-term power-law rehydroxylation kinetics’ has been published online and is due to appear in a future edition of Proceedings of the Royal Society A. A copy of the paper is available on request [ver más abajo nota de prensa de la publicación, ayer mismo].

The full research team comprised Dr Moira Wilson, Dr Margaret Carter, Prof William Hoff,

Ceren Ince, Shaun Savage and Bernard McKay from The University of Manchester, Professor Chris Hall from the School of Engineering and Centre for Materials Science and Engineering at The University of Edinburgh and Ian Betts from The Museum of London. The Canterbury Archaeological Trust provided additional samples and information for the study while Ibstock Brick Ltd provided kiln-fresh bricks.

............

Más info: Seminario habido el 12 de marzo pasado en la School of Engineering and Centre for Materials Science and Engineering de la Universidad de Edimburgo:

Prof. Chris Hall

Institute for Materials and Processes, University of Edinburgh

“Old bricks: dating fired-clay ceramics using long-term power-law r...

Fired clay materials like brick, tile and ceramic artefacts are found widely in archaeological deposits. The slow progressive chemical recombination of ceramics with environmental moisture (rehydroxylation) provides the basis for a method of archaeological dating. Rehydroxylation rates are described by a (time)1/4 power law. A ceramic sample may be dated by exposing it to water vapour to measure its mass gain rate and hence its individual rehydroxylation kinetic constant. The kinetic constant depends on temperature. Mean lifetime temperatures are estimated from historical meteorological data. Calculated

ages of samples of established provenance from Roman to modern dates agree excellently with assigned (known) ages. This agreement suggests that the power law holds precisely on millenial timescales. The power law exponent is accurately ¼, consistent with the theory of fractional (anomalous) 'single-file' diffusion.

.....................

El artículo, en efecto, ha sido publicado con fecha de ayer en la citada revista, aquí la nota de prensa de la misma:

"FIRE AND WATER REVEAL TRUE AGE OF ANCIENT RELICS"

20 May 2009

Fire and water are all that is needed to unlock the internal clocks' of archaeological remains and accurately reveal their age, say scientists. The research, published online today in Proceedings of the Royal Society A , will help archaeologists date remains that are thousands of years old, and also reveal where other techniques go wrong.

Dating methods are of paramount importance in the earth and environmental sciences, palaeontology, archaeology, and art history. Fired clay material such as bricks, tile and ceramics represent an important sample of the remains unearthed at archaeological digs, but they are notoriously hard to date accurately (**). Carbon 14 dating, which can be used on bone, does not work with ceramics, and those techniques that do exist are extremely complex.

Now a team of scientists from the Universities of Manchester and Edinburgh have found a surprisingly simple way to get around this issue.

From the moment they are fired, ceramics begin to absorb moisture from the environment which causes them to gain mass. Using a technique they call rehydroxilation dating' researchers led by Dr Moira Wilson from the University of Manchester found that heating a sample of the relic to extreme temperatures causes this process to be reversed all the moisture it has gained since it was fired is lost again.

The more weight a sample loses during heating, the more moisture there was to start with, and so the older the relic. After heating, Wilson and her team used an extremely accurate measuring device to monitor the sample as it began to recombine with moisture in the atmosphere. They then used a law to predict how long it would take for all the water lost in heating to be reabsorbed, and so reveal the true age of the sample.

To test their new technique the scientists teamed up with the Museum of London and tried it out on samples of know age. They successfully dated brick samples from the Roman, medieval and modern periods, and the method was so accurate that it looks to become the way in which such artefacts are dated in the future, according to Wilson.

So far, the technique has been used with specimens that are as much as 2000 years old, but has the potential to be used on much older artefacts, says Wilson, even those dating back 10,000 years.

What's more, the technique has revealed a flaw in previous dating verdicts. When clay objects are submitted to extreme temperatures, and moisture removed, this internal clock' is reset. That means that objects that have been subjected to extreme heat, such as those dating back to the WWII Blitz are often, in truth, much older.

The technique has far reaching implications. "As well as the new dating method, there are also more wide-ranging applications of the work, such as the detection of forged ceramic," says Wilson. "The method could also be turned on its head and used to establish the mean temperature of a material over its lifetime, if a precise date of firing were known," she adds, which could make the method a useful tool for climate change studies.

...............

(*) Por el momento no he encontrado nada en español sobre esta noticia (no es del tipo que se preste a llamar mucho la atención de la prensa, o a titulares llamativos). Para lectores que tengan alguna dificultad con la lengua, dos muy aceptables traductores de textos en inglés (y otras lenguas), por ejemplo, en El Mundo y Ya.com. Para términos concretos el sitio de Word Reference, con otros recursos.

(**) Se refieren a materiales de fechas más problemáticas o no bien datados por estratigrafía; habría que exceptuar, pues, algunos tipos, como las cerámicas áticas de figuras negras y rojas, la mayoría de las sigillatas romanas o, en el caso de los ladrillos, los bien fechados a través de "bolli laterizi", por ejemplo, en los que la prueba sería superflua.

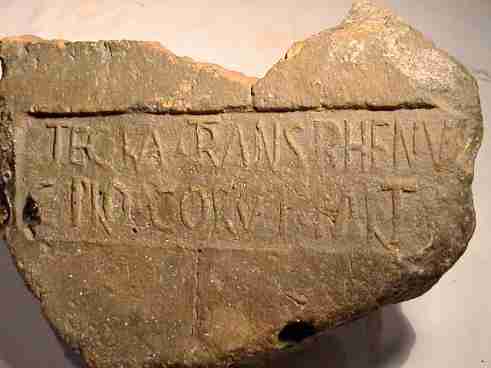

Complemento: Excelente sitio para ladrillos legionarios, sellados o inscritos, en Inglaterra y otras zonas europeas con acuartelamientos romanos aquí, en Roman Coins.

© Fotos insertadas: Roman Coins y Wikipedia.

Fuente de la noticia: N. Thorpe, en la lista Britarch, a través de J. Valdez, en Archport.

-

Comentario por Yrg el mayo 22, 2009 a las 1:59pm

-

Es una muy buena noticia; pero no explican si tiene en cuenta la diferente exposición a la humedad que tienen los ladrillos o cerámicas enterradas bajo tierra por siglos, o si deben aplicarse diferentes patrones para hallazgos con humedad menor a la inglesa (Carthago, Ur...).

-

Comentario por Alicia M. Canto el mayo 24, 2009 a las 4:59pm

-

Gracias.

-

Comentario por andrea el mayo 25, 2009 a las 1:03am

-

Dra. Canto: Hace unos días hice un comentario a esta noticia, que borré, posteriormente, porque pensé que se prestaría a un montón de comentarios "paradoxos" y no quise que se emborronara este artículo. Cuando quise explicar esta cuestión, se terminó de estropear todo mi "aparataje" informático, pero ahora que "nos hemos recuperado", y aún a riesgo de que suceda, me parece importante que se preste atención a las fotografías de materiales constructivos con epígrafes impresos e incisos ante coctionem que ha incluido en este artículo.

-

Comentario por Alicia M. Canto el mayo 25, 2009 a las 1:07am

-

Andrea: Me alegro de su "recuperación", y de que al menos alguien se diera cuenta de mis intenciones al respecto de las fotos, ¡aunque nunca los que necesitarían de verdad dársela, que son como un frontón! ;-)

-

Comentario por Alicia M. Canto el junio 12, 2009 a las 1:09am

-

Bueno, ya va habiendo algo más en español sobre esta nueva técnica, aunque poco:

- Artículo en Wikipedia (27-5-2009): Rehidroxilación

(buenas referencias en inglés; no bien categorizado, en "Tecnología prehistórica")

- Noticia en http://www.amazings.com (10-6-2009):

Arqueología

Nuevo Método de Datación Arqueológica Para Objetos de Cerámica

10 de Junio de 2009

Un equipo de científicos ha desarrollado una nueva forma de datar objetos arqueológicos valiéndose del fuego y el agua para acceder a sus "relojes internos". Este método simple promete ser una técnica de datación tan importante para objetos de cerámica como lo es la datación por radiocarbono para materiales orgánicos como el hueso o la madera.

La nueva técnica, descubierta por expertos de la Universidad de Manchester y de la Universidad de Edimburgo, puede ser utilizada en arcilla horneada, así como en ladrillos, baldosas y objetos de alfarería.

Trabajando con el Museo de Londres, el equipo fue capaz de datar muestras de ladrillos de los periodos Romano, Medieval y Moderno con notable precisión.

Los investigadores han establecido que su técnica puede ser utilizada para determinar la edad de objetos de hasta 2.000 años, pero consideran que tiene el potencial para fechar objetos con cerca de 10.000 años de antigüedad.

El método se basa en el hecho de que un material cerámico de arcilla horneada comienza a reaccionar químicamente con la humedad atmosférica tan pronto como se le saca del horno. Este proceso químico continúa durante toda su vida causando que gane peso: Cuanto más antiguo sea el material, más peso habrá ganado.

En el año 2003, el equipo de las universidades de Manchester y Edimburgo descubrió una nueva ley que define de forma precisa cómo varía con el tiempo la velocidad de la reacción entre la cerámica y el agua.

La aplicación de esta ley es la base del nuevo método de datación, debido a que la cantidad de agua que se combina químicamente con la cerámica proporciona un "reloj interno" al cual se puede acceder para averiguar su edad.

El uso de la técnica implica medir la masa de una muestra de la cerámica y luego calentarla hasta cerca de 500 grados centígrados en un horno, lo cual elimina el agua.

La muestra es luego examinada con un dispositivo de medición de muy alta precisión conocido como microbalanza, para determinar la velocidad exacta a la que la cerámica se

combina con el agua según transcurre el tiempo.

Valiéndose de este mismo factor tiempo, es posible extrapolar la información obtenida para calcular el tiempo que el material tardará en recuperar la masa perdida por el calentamiento, revelándose así la edad de la muestra.

La autora principal de esta investigación es Moira Wilson.

Información adicional en:

* U. Manchester

Comentar

Bienvenido a

Arqueologia, Historia Antigua y Medieval - Terrae Antiqvae

TRANSLATE BY GOOGLE

Recibe en tu correo los últimos artículos publicados en Terrae Antiqvae -Boletín Gratuito-

Publicidad by Google

Lo más visto

Síguenos en Redes Sociales: Facebook y Twitter

¡Gracias por visitarnos! ¡Bienvenid@!

© 2025 Creado por José Luis Santos Fernández.

Tecnología de

![]()

¡Necesitas ser un miembro de Arqueologia, Historia Antigua y Medieval - Terrae Antiqvae para añadir comentarios!

Participar en Arqueologia, Historia Antigua y Medieval - Terrae Antiqvae